Cowboy-Knight

Examining the reality and mythology of cowboys, and asking who gets to be a cowboy today.

While reading about the American West, there's one figure I keep encountering: the brave white cowboy, riding his majestic horse over seemingly uninhabited wilderness, dazzling everyone he meets with his charm and his grit. A knight in denim jeans and silver spurs. It's interesting that I keep running into him because, dazzling though he may be, he's not real. Or rather, this archetypal cowboy has only a tenuous connection to the cowboys of the 1800s. J. Gray Sweeney writes in his (phenomenal) essay Racism, Nationalism, and Nostalgia in Cowboy Art:

What is so amazing about America's fascination with the cowboy is that there has been such an enormous feast on so little food. [...] Although the myth of the cowboy hero represented him as white, in reality he was usually black or brown. He was often a former slave or a vaquero, or a descendent of slaves or vaqueros. The daily reality of the cowboy's life was virtually unending hard work - hot and dry in summer, cold and wet in winter. [...] A depiction of a tired cowboy with glasses and bad teeth - an 'anti-hero' - is not generally a popular subject for cowboy artists.

This "virtually unending hard work" isn't an exaggeration. In Mark A. Lause's The Great Cowboy Strike, he details the cowboy's 108-hour workweek (!) and the grueling days on a cattle drive. Contrary to popular imagination, individualism “proved incapable of managing massive herds of cattle, a process that encouraged teamwork and solidarity." This hard labor was almost considered a noble rite of passage by young men, and some would later look back on this time fondly. Still, many cowboys were homeless, and few returned season after season unless they had no other options.

Curiously, there weren't that many cowboys, no more than a few hundred at a time. But even in their heyday they "tapped into the romance of an older, upper-class equestrian tradition" (Lause). This budding myth of cowboy as modern-day chivalric knight took hold in classic Western art, like the paintings of Remington and Schreyvogel. These painters weren't painting real cowboys. Remington was deeply racist and dismissive of non-white cowboys, and Schreyvogel mostly worked out of a studio in New Jersey. But the cowboy-knight they created, a white man on horseback who was more concerned with adventure than cattle drives, has come to dominate the imagination. Less heroic Western paintings like "Morning of a New Day" by Henry Farny, which depicts Native Americans marching through a snowy mountain pass while a train speeds past them, are still not as popular today: when this painting was submitted to be the cover image of a Western art publication, it was rejected because "people won't buy a catalogue with cold and hungry Indians on the cover as readily as one with cowboys." (Sweeney)

Hollywood played a heavy role in perpetuating this romanticism, though funny enough the first Western, an 1899 short called "Kidnapping by Indians", was filmed in Britain. As that movie's title suggests, Westerns started off with fairly simple plots. The 1903 film "The Great Train Robbery" is about exactly that. Eventually these stories of outlaws and sheriffs got mixed in with the chivalric romance of cowboys until Westerns became an especially powerful vehicle of propaganda. In 2008 the American Film Institute named "The Searchers" (1956) the greatest American Western. Playing off the same fears as "Kidnapping by Indians", "The Searchers" tells a story of a young white woman kidnapped by Comanches, and the heroic cowboy-knight, played of course by John Wayne, who has to save her. It's a dull movie, relying heavily on stereotypes that by 2008 should have been recognized as unimaginative to say the least. But the fact that it's seen as an exemplar of the genre is telling. For many Americans, John Wayne (real name Marion Robert Morrison) galloping around Monument Valley (real name Tsé Biiʼ Ndzisgaii in Navajo) is the canonical cowboy.

Lause argues that much of this Hollywood myth-making is "aimed at an ongoing affirmation of legitimacy that requires the projection of violent intentions onto the designated targets of institutionalized violence." Put more simply, these classic Westerns were an effort to justify the U.S. government's unjustifiable cruelty in the American West. By creating this enchanting cowboy-knight, based somewhat on reality and somewhat on European imagination, the conquest of the West was white-washed and in many ways forgotten. Hollywood proved it was surprisingly easy to distract us from the horrors of manifest destiny by telling stories of adventurous cowboys, and I'd argue that to this day, most Americans know more about Westerns filmed in the '60s than they do about the Native American tribes whose land they're living on.

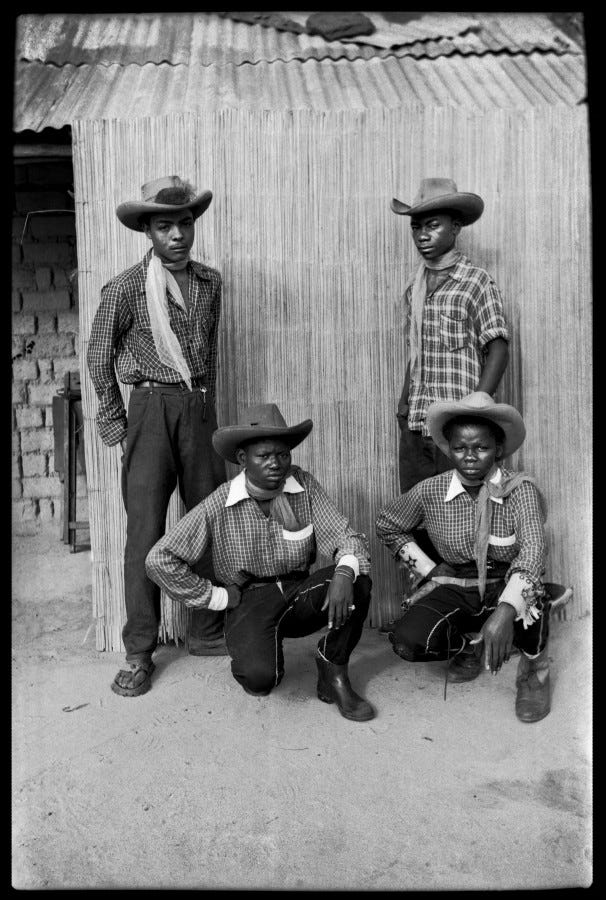

But as with many symbols, the cowboy doesn't just represent one thing. While he may have started as another tool of American imperial propaganda, for many people he also represents freedom, self-sufficiency, even beauty. Westerns weren't just popular in America; in the '50s, a few of them made it to the Congo, where kids and teens were so captivated by characters like the Lone Ranger that they started dressing like cowboys, too. In this wonderful interview with Professor Ch. Didier Gondola, he argues that the archetype of the manly, capable cowboy offered an alternative to the colonialist stereotypes the Belgians imposed on the Congolese as being infantile or weak. These kids in Kinshasa weren't weak, they had grit! And they had the cowboy hats to prove it.

Almost as long as there have been Westerns, there have been Anti-Westerns, too. These movies and books take a critical look at the cowboy-knight, giving him more complex desires and motivations that have been lacking in the propaganda pieces. One of the most famous, Blood Meridian by Cormac McCarthy, is known for its bleak and violent portrayal of the West. His cowboy figures are no heroes, and it's probably for the best if you don't really identify with any of them. But his book is a useful counterweight against the cowboy-knight, and not every Anti-Western is as grim. Movies like “Brokeback Mountain” and “Django Unchained” offer us a new type of cowboy hero, one who perhaps is more relatable than a stoic John Wayne.

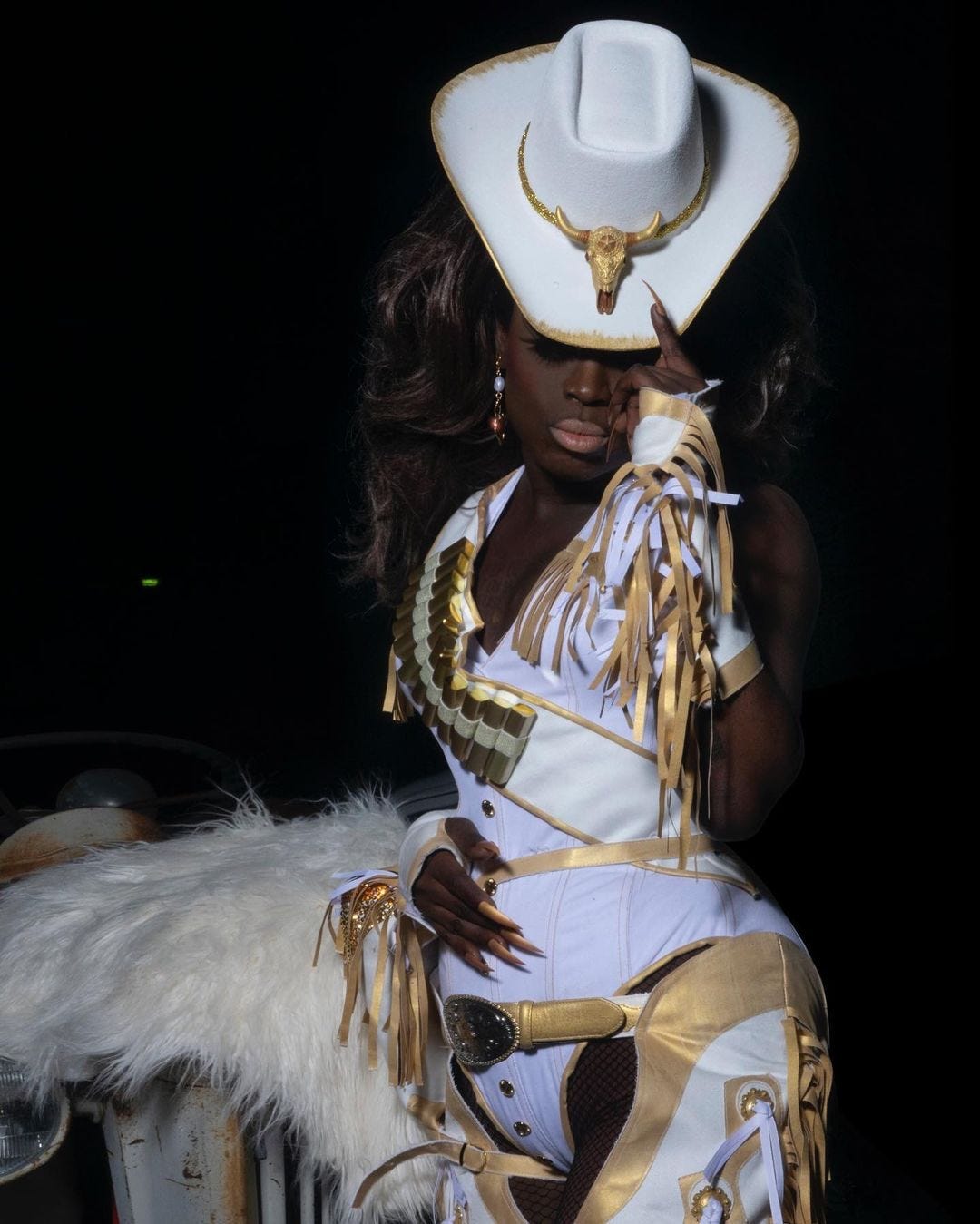

Today we're offered even more variations of what a cowboy can be. The Yee-Haw Agenda, created by Bri Malandro, celebrates how the "cowboy aesthetic" can be Black, feminine, queer. Musicians like Lil Nas X, Kacey Musgraves, and Orville Peck have done the same for country music, and their songs and music videos play with cowboy tropes in refreshing ways. And of course, real cowboys still exist today. John Ferguson's photo series, The Forgotten Cowboys, is a much more accurate and nuanced portrayal of cowboys than anything Remington ever painted. In Compton, the Compton Cowboys are "highlighting the rich legacy of African-Americans in equine and western heritage". In some ways these "new" portrayals of cowboys are actually a return to the old truth, that cowboys weren't any one type of person, and certainly not just a John Wayne. Far from being doomed as a symbol of American white nationalism, the cowboy has been reborn as a patron saint of anyone who wants to buck convention and needs wide open space for all their dreams. He’s still a romantic figure, a daydreamer in a prairie, but now we all get to daydream, too.

I am so glad I stumbled upon this thread. I moved to a 5 acre farm in 1976 in Flora Vista NM from LA CA as a 12 year old. The first grown man cowboy I met was named Joe Ulibari, a Mexican dude. He was the coolest, baddest, most awesome man I had ever seen. Full cowboy regalia, man and horse. I learned so much from him about what is means to be a cowboy. I also met many Navajo and Hopi cowboys. I also met a cowboy named Curtis, white man. He was a bullrider and all-around rodeo champ. My John Wayne ideal of him was fractured when our gang of young cowboys happened upon him tanning on his patio with a metal tan-shield in a white robe (with shorts, not a pedo!) It made me realize all the Hollywood stuff was BS. Cowboys are as you say, they are made in our own minds and express our own ideals of that vision. Thanks for writing this, and I can't wait to read more. I write about my cowboy-self at riclexel.substack.com