Two hours east of Los Angeles, where the suburbs abruptly end and the I-10 snakes through the dusty nothingness between San Gorgonio Mountain and Mount San Jacinto, lies the unincorporated community of Cabazon (pop. 2,629). It boasts exactly two things: the Cabazon Dinosaurs (strange monuments to creationism featured in Paris, Texas (1984) and Pee-wee's Big Adventure (1985)) and a couple of Tesla Superchargers. A Tesla driver needing to recharge outside of LA could also stop in Twentynine Palms, Cathedral City, Indio, Needles, Quartzsite... an endless network of Tesla Superchargers sprawl out across the desert.

Wherever the Tesla driver goes off to next, it's unlikely they'd be cruising southeast down the 111 to the Salton Sea, because no one goes to the Salton Sea. There's plenty of popular tourist spots around it: Joshua Tree, Palm Springs, Anza-Borrego, and Salvation Mountain all encircle it. But many Californians don't really know anything about the Salton Sea itself, or if they do they treat it with distant pity. "Isn't that where all the birds died?" they might ask, before quickly changing topics. It's a complete ecological disaster and one we're eager to forget.

Yet for millions of years, the Salton Sea wasn't any kind of disaster, nor a sea for that matter. It was just a simple basin that would periodically fill with water from the Colorado River, before drying out again as the river changed course. This cycle was normal, and also important; we'll come back to it.

By the mid-1800s the basin had been dry for a long time, earning the evocative name "the Valley of the Ancient Lake". Apparently unmoved by the poeticism of barren landscapes and not wanting to let any scrap of them go unused, in 1900 California governor James Budd approved an irrigation project to divert water from the Colorado River into the "Salton Sink", making the area fertile ground for farming. The canal gradually filled with silt until it flooded in 1905, causing water to rush into the basin and submerge an entire town and Torres-Martinez (Mau-Wal-Mah Su-Kutt Menyil) Native American land.

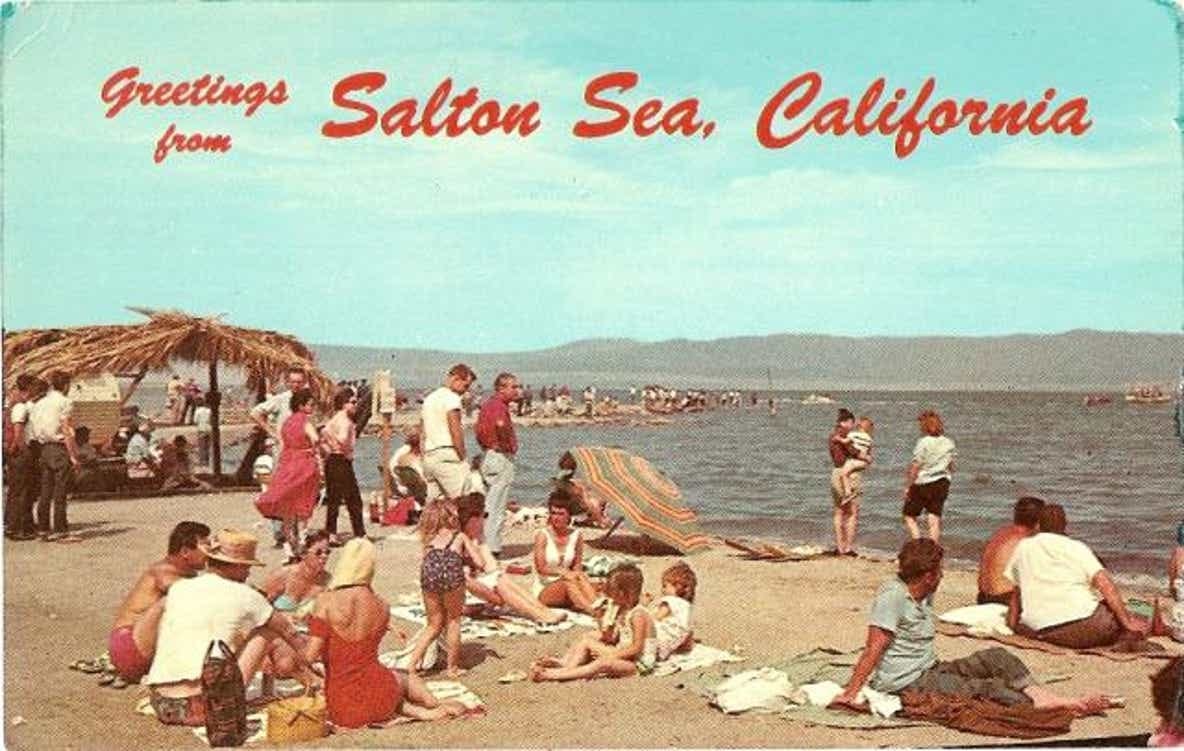

Californians evidently decided this was fine and, undeterred by the folly of farming in the desert, kept diverting water from the Colorado River, thus never letting the lake dry up as it used to. Eventually this artificial oasis attracted its own ecosystem of fish and migratory birds, which attracted birdwatchers, tourists, and even celebrities. The area became so charming that by the 1950s the Salton Sea had transformed into a resort town where the likes of Frank Sinatra and The Beach Boys performed. This man-made oasis must have seemed like a miracle.

So how did it become the ecological disaster we choose to uncomfortably ignore today?

First let's consider salt. Most soils have a little bit of salt in them. As water moves through the soils, like the Colorado River moves through the desert, it picks up some of that salt. It's not a lot, but it's there. That water continues coursing its way through the landscape and eventually it may end up somewhere with no place to go, like a terminal (endorheic) basin. All it can do now is evaporate, leaving that salt behind.

Second let's consider nitrogen. A lot of water systems are "nitrogen-limited". But fertilizers have a lot of nitrogen. And where there's agriculture, there's agriculture runoff. The nitrogen on farms ends up in the water and now the water isn't so nitrogen-limited after all. This is how we get bacteria blooms, which then use up all of the oxygen in the water, leaving none for the rest of the ecosystem.

Well the Salton Sea just so happens to be a terminal basin with a lot of agriculture around it. Letting the Salton Sea stay flooded after 1905 meant that those ancient salt deposits dissolved into the water, increasing its salinity over the course of decades. It took a while to be harmful to the fledgling ecosystem, but combined with some agriculture runoff disasters and the subsequent bacteria blooms, eventually life no longer stood a chance.

Now the Salton Sea is just another desert wasteland. Other than a documentary delightfully narrated by John Waters, it hasn't received much attention in the last few decades. We've all, subconsciously or otherwise, decided this land doesn't matter. But the West is the West, and all land has to be catalogued, extracted, and made profitable. And what better way to squeeze just another drop out of an already-brutalized land than to start mining it? Hey, maybe for some lithium for that Tesla battery?

◎

When I was visiting Anza-Borrego Desert State Park this past winter, I hiked with a man who lives next to the Salton Sea, just about 40 minutes away. He told me the sea is in the poorest county in California (by some metrics, other counties claim that title, but poverty is poverty and for the richest state in the union, California is rife with it). He also told me that governor Gavin Newsom had recently approved a lithium mining operation there. Apparently it'll be eco-friendly, clean up the sea, revive the fish, bring money into the area, provide green energy, and be a clear win-win-win for everyone involved. The man seemed skeptical.

I'm also skeptical. Lithium mining is not particularly eco-friendly to begin with. One lithium mine in Nevada is "expected to use billions of gallons of precious ground water, potentially contaminating some of it for 300 years, while leaving behind a giant mound of waste." I'll remind you that Nevada is a desert and doesn't have an abundance of water, though of course that hasn't stopped lithium mining in other arid regions like in Chile and Bolivia, where water is also sacrificed in order to extract lithium.

As an alternative to this, some people are considering deep sea mining, even though we don't fully understand the implications of it yet and what we do understand isn't looking good:

Put simply, we have no idea what kind of cascading effects DeepGreen’s extraction process might set off. So little happens in the deep sea that large scale sediment disruptions could be catastrophic. Removing the nodules is only one step; the resulting wastewater will also have to be disposed of and could damage miles of midwater ecosystems.

More insidiously, we also have to consider that all of these operations happen in poor regions out of sight and out of mind of the wealthy people who will be the ones using all these resources. Newsom ostensibly approved this mine partially to economically rejuvenate the region and help its residents, but despite California's reputation as some kind of progressive utopia, this is the same state where poor people of color live with radioactive waste, police traumatize and displace the unhoused, and migrant farm workers are expected to be out in the fields even during brutal fires. If so many poor Californians are considered disposable, will the residents of the Salton Sea really be the exception? Would we even be considering lithium mining if we could only extract it near Malibu or Palo Alto?

Now you might want to argue that this lithium mine really will be environmentally sound, and Newsom really does want to help the citizens of one of California's poorest counties, and I would love for all of that to be true. But we'd be debating with the unspoken assumption that this lithium mine is necessary in the first place. What if we stepped back and questioned that assumption? (I'll save the question of whether we should help poor communities for their own sake without demanding further sacrifices from them as a moral thought exercise for the reader.)

We have a tendency to believe in the inevitability of our way of life. Surely human civilization is a steady march towards... something, maybe we'll find out when we get there, but it's definitely always going forward. We used to wander around in bands of 150 people who ate bugs and now we rely on cars and Twitter, and our future will be just doing that but better I guess. At any rate, we can't backpedal.

In their profoundly wonderful and engaging book The Dawn of Everything, David Graeber (rest in peace) and David Wengrow argue that actually, human civilization can look like anything, and nothing is inevitable. Societies did indeed backpedal: even agriculture, which we assume demarcates a clear before and after in human history, was sometimes abandoned as people returned to hunting and gathering when it made sense to do so. We can try things and change our minds and go back to an older way of life, or imagine yet another one.

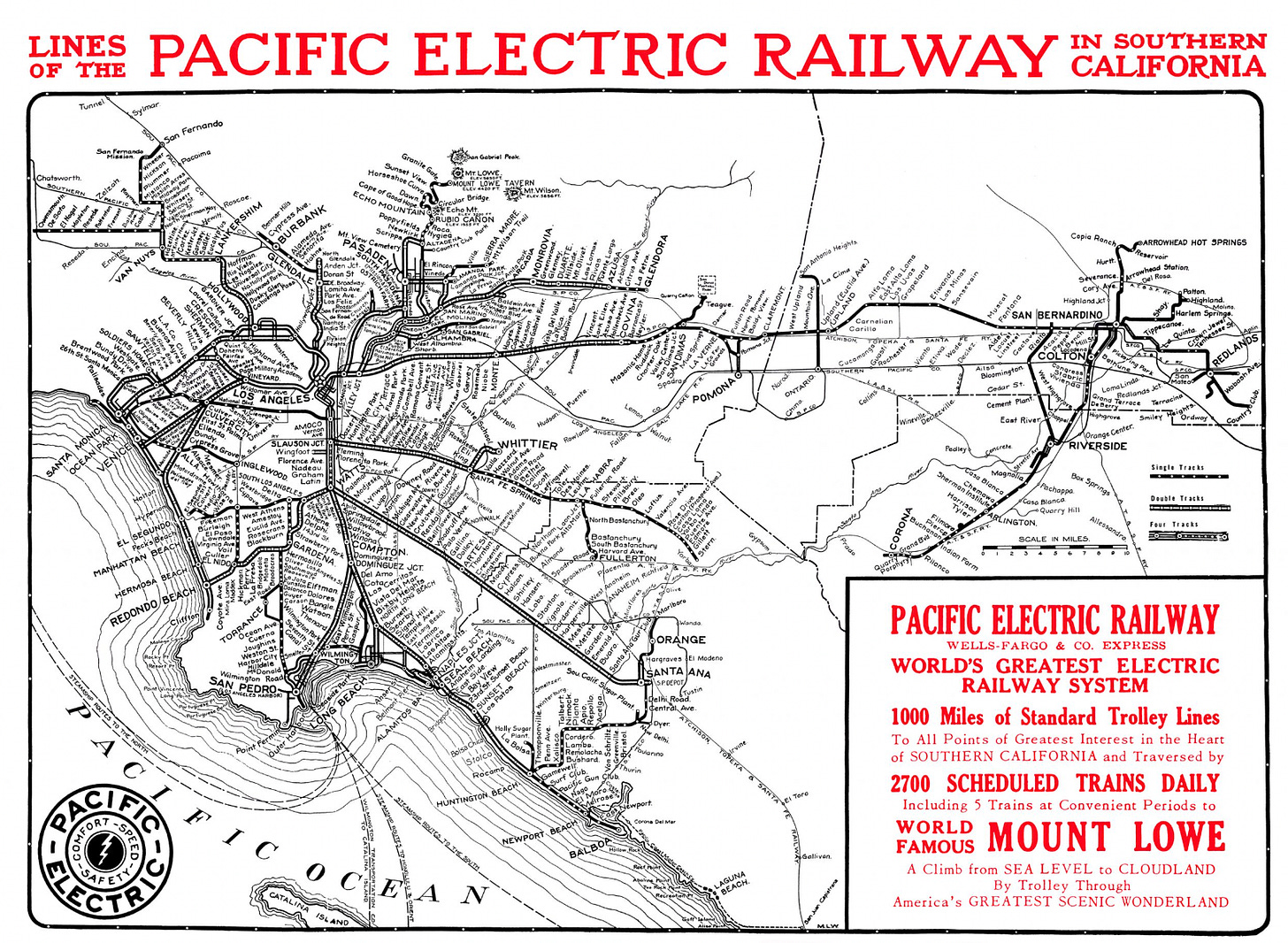

Right now we "need" lithium mines because we "need" electric cars because we "need" cars in general. But... do we actually? To be clear I truly don't fault anyone for owning a car, Tesla or otherwise. I conceived of this very newsletter while on a 3,000 mile roadtrip through the West, and also it is so hard to try to live more sustainably when most cities aren't walkable or bikeable, everything is covered in plastic, and you need a smartphone (another mining nightmare) to do anything. But in our search to find a more sustainable way of life, I want us to consider all the options, instead of assuming that relatively new "necessities"—cars, Twitter, etc—have to be permanent fixtures in our future. If we have to keep propping up extractive, polluting industries that create new cycles of problems so that we can hold onto something that didn’t even exist for most of human history, perhaps the easiest way forward will be to do what our ancestors have always done and just backpedal.

◎

The Hetch Hetchy Valley in Yosemite National Park was once considered as beautiful as the Yosemite Valley itself, perhaps even more so, at least to John Muir. Beauty notwithstanding, it was flooded in 1923 to create a reservoir for San Francisco. Maybe this was right, maybe it wasn't, but in any case it was a permanent change to an ancient landscape. The West is full of these changes; the dwindling Colorado River alone shows how much we're willing to modify and abuse the land past what it can sustainably offer us. Lithium mining around the Salton Sea (and in Nevada, South America, and everywhere else it happens) will also irrevocably change the land.

While there's a chance that lithium mining and other "green" solutions will solve all our problems, there's a notable chance that they won't, and in our rush to combat climate change we risk doing more damage. The solution to "cars pollute" isn't necessarily "cars that pollute in a different way" but maybe "no cars". There may not be any sustainable way to maintain our 21st century lifestyles. Maybe we have to make fewer demands of the earth instead, and adapt to its slow rhythms. After all, these rhythms had been working pretty well for the Salton Sea for millions of years. Can't hurt to try.

I want to give a special shoutout to my friend Lukas, a scientist who kindly answered all my questions about the Salton Sea and why it is what it is today; I would never have known what an endorheic basin is without him. He writes his own newsletter about landscapes and environmental science that I often find moving, and in many ways this piece is the result of years of conversations with him.

I also want to thank everyone who has listened to me ramble about lithium mining for the last few months. I’ll finally move on now, thank you for your patience.

A great deep dive! I don’t claim to know, but I can’t see how people living in this area want or need a lithium mine in their backyard. But hey, let’s add one new ecological disaster onto the back of another. Ps - I drove through the area once, the Skii-In was a really fun place to stop. I don’t think I had a cheaper meal while travelling through California.